Where Does It Come From, cont: the 70’s Infusion of the Eccentric

By the early 1970’s, comics had a “modern” take on superheroes down pretty solidly. Masters like Kirby, Buscema, Romita, and Swan knew exactly what they were about and how to get a super-punch across with maximum wallop in Superman, Fantastic Four and Spider-man comics. And as a kid, I drank it all up. But unbeknownst to me what was missing, in large, from comics (and remember, back then it was pretty much DC, Marvel or nothin’) was the sense of the quirky, the unique, personal vision and style in comics. There was no EC, to nurture a stable of obsessive perfectionist, free-spirit artists, no multitude of smaller publishers who would grab up the “oddballs” and see what worked. No sense of the experimental, the joy of discovering the strange and fresh that, unpredictably, simply worked.

By the early 1970’s, comics had a “modern” take on superheroes down pretty solidly. Masters like Kirby, Buscema, Romita, and Swan knew exactly what they were about and how to get a super-punch across with maximum wallop in Superman, Fantastic Four and Spider-man comics. And as a kid, I drank it all up. But unbeknownst to me what was missing, in large, from comics (and remember, back then it was pretty much DC, Marvel or nothin’) was the sense of the quirky, the unique, personal vision and style in comics. There was no EC, to nurture a stable of obsessive perfectionist, free-spirit artists, no multitude of smaller publishers who would grab up the “oddballs” and see what worked. No sense of the experimental, the joy of discovering the strange and fresh that, unpredictably, simply worked.

All that changed with the emergence of a new generation of comics writer/editors, like Len Wein, Roy Thomas and Marv Wolfman, who opened the door to some new artists whose styles drew from more diverse and historic sources that the generation that was then pushing the pencils on the comic mainstay titles.

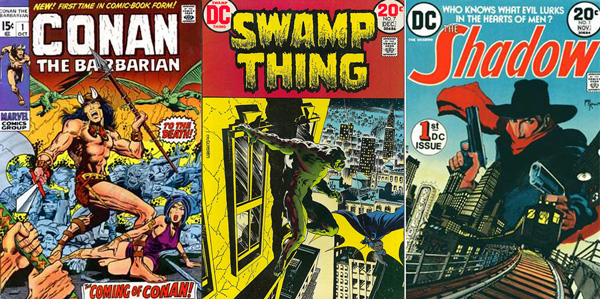

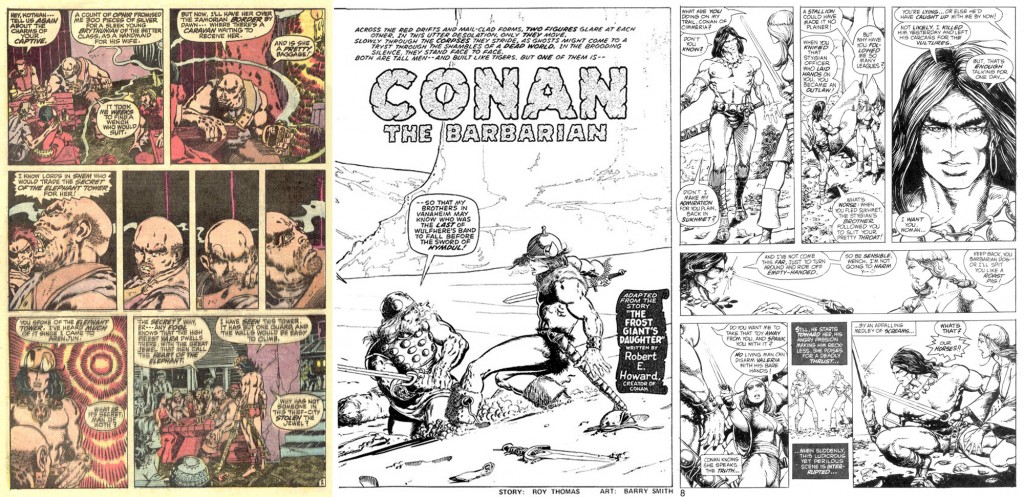

Barry Windsor-Smith slipped in the door at Marvel on a few issues of Daredevil and Avengers by doing a fairly poor imitation of Kirby crossed with Steranko. But, once he was given the task of envisioning Conan from a clean slate in 1970, his own, very personal style blossomed quickly. It was exhilarating to pick up each new Conan issue, and see the quantum leaps Smith’s art took each month as he drew ever more heavily from influences of classical European artists and the great the Romantics. Above, samples from what I’d call early, mid and late-stage work from his Conan run. The early flair and brashness work through quickly to a powerful balance of bold design coupled with an elegance of linework.

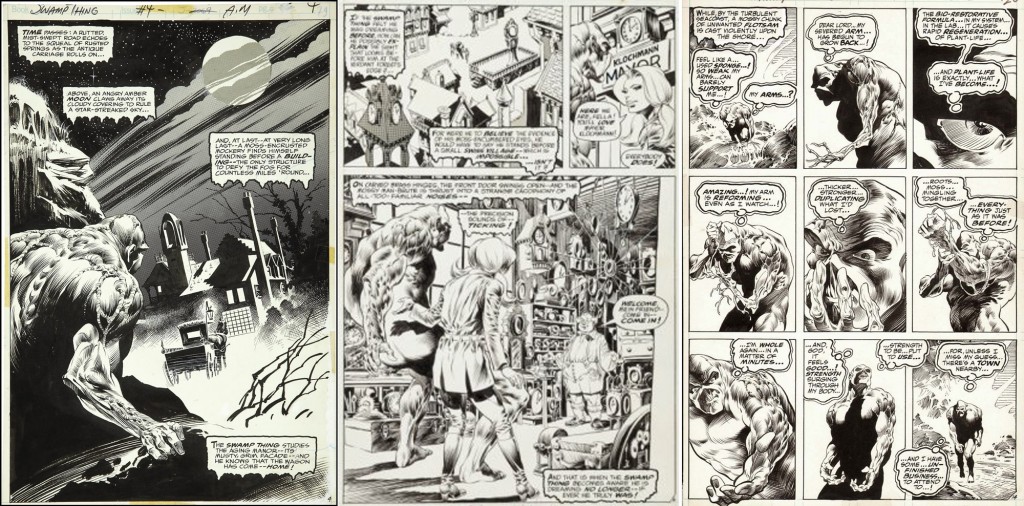

Barry Windsor-Smith slipped in the door at Marvel on a few issues of Daredevil and Avengers by doing a fairly poor imitation of Kirby crossed with Steranko. But, once he was given the task of envisioning Conan from a clean slate in 1970, his own, very personal style blossomed quickly. It was exhilarating to pick up each new Conan issue, and see the quantum leaps Smith’s art took each month as he drew ever more heavily from influences of classical European artists and the great the Romantics. Above, samples from what I’d call early, mid and late-stage work from his Conan run. The early flair and brashness work through quickly to a powerful balance of bold design coupled with an elegance of linework. Speaking of elegance in linework, you can’t avoid Bernie Wrightson, who entered comics maybe a year or so after Windsor-Smith, bringing to many young eyes (like my own) our first view of the lush, sensual, super-humanly precise linework and feathering that clearly harkens back to many of the EC masters, particularly “Ghastly” Ingles and, of course Frank Frazetta. It was graceful, evocative, powerfully atmospheric and, like Windsor-Smith, miles removed from the comic art I was used to seeing.

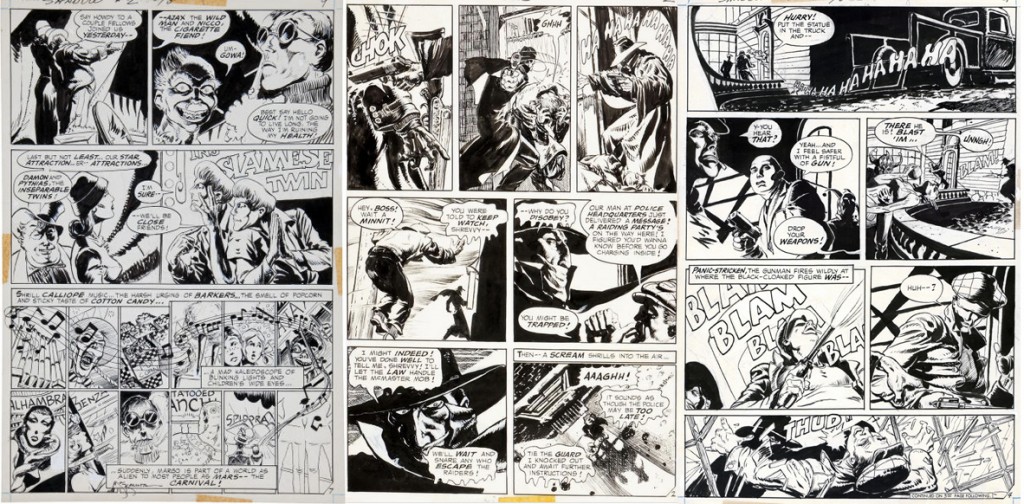

Speaking of elegance in linework, you can’t avoid Bernie Wrightson, who entered comics maybe a year or so after Windsor-Smith, bringing to many young eyes (like my own) our first view of the lush, sensual, super-humanly precise linework and feathering that clearly harkens back to many of the EC masters, particularly “Ghastly” Ingles and, of course Frank Frazetta. It was graceful, evocative, powerfully atmospheric and, like Windsor-Smith, miles removed from the comic art I was used to seeing. Mike Kaluta’s work began appearing around the same time, and was perhaps the most eccentric of them all. His work seemed to have nothing at all to do with the comics being produced all around him. His work harkened back to the roughshod illustrations from the classic “pulp” stories of the 1930’s. So, he was a perfect fit for DC’s launch of their Shadow comic. Like Windsor-Smith and Wrightson, Kaluta’s way of approaching figure drawing, conveying motion, action and character were drawing from very different sources that the mainstream artist of the day.

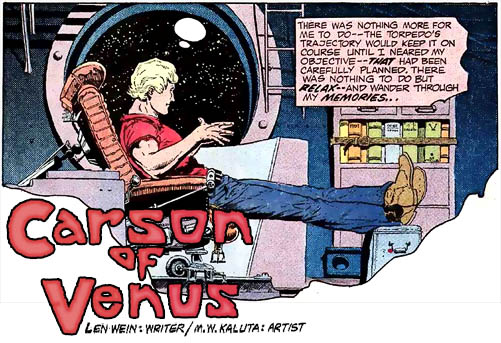

Mike Kaluta’s work began appearing around the same time, and was perhaps the most eccentric of them all. His work seemed to have nothing at all to do with the comics being produced all around him. His work harkened back to the roughshod illustrations from the classic “pulp” stories of the 1930’s. So, he was a perfect fit for DC’s launch of their Shadow comic. Like Windsor-Smith and Wrightson, Kaluta’s way of approaching figure drawing, conveying motion, action and character were drawing from very different sources that the mainstream artist of the day.

To my eyes, it was all revelatory and spoke to a much wider range of what was possible to express on a comics page than I’d ever envisioned. Those notions didn’t stop my from consciously trying to achieve a “mainstream style” as I was trying to work my own way into the business of drawing comics, but I think they planted some seeds in me that always kept me yearning for something, however subtle, that was a bit at odds with a purely “conventional” approach in the comics I drew. And I suspect they might have worked a similar effect on many of the artist who started working in the field around the time I did as well. But, I’ll leave it up to them to own up to their influences! One last anecdotal note: Kaluta was a particular inspiration to me in one other way. Early on, he drew the back-up in DC’s “Korak, Son Of Tarzan” book. it was the less well-known Burrough’s tale “Carson of Venus”. I was a huge fan of Kubert’s Tarzan, of course, so picked up the Korak book out of curiosity. Kaluta’s art on that back-up story was so unique and so enjoyable that it kept me buying the title despite an indifference to the lead feature. A few years latter, when I got the call to draw the Barren Earth back-up feature in DC’s Warlord book, I strived to make the art similarly compelling and unique. I don’t know to what end I might have achieved that goal, but I was gratified a few years back at a convention to be told buy a fan that they had indeed bought the Warlord book just to read our back up story. So, for that extra dose of motivation to reach for a unique comics voice, a very special “Thanks” to Mike Kaluta.

One last anecdotal note: Kaluta was a particular inspiration to me in one other way. Early on, he drew the back-up in DC’s “Korak, Son Of Tarzan” book. it was the less well-known Burrough’s tale “Carson of Venus”. I was a huge fan of Kubert’s Tarzan, of course, so picked up the Korak book out of curiosity. Kaluta’s art on that back-up story was so unique and so enjoyable that it kept me buying the title despite an indifference to the lead feature. A few years latter, when I got the call to draw the Barren Earth back-up feature in DC’s Warlord book, I strived to make the art similarly compelling and unique. I don’t know to what end I might have achieved that goal, but I was gratified a few years back at a convention to be told buy a fan that they had indeed bought the Warlord book just to read our back up story. So, for that extra dose of motivation to reach for a unique comics voice, a very special “Thanks” to Mike Kaluta.

AL WILLIAMSON

AL WILLIAMSON JEREMY COLWELL

JEREMY COLWELL JOE KUBERT

JOE KUBERT MARK SCHULTZ

MARK SCHULTZ PAUL CHADWICK

PAUL CHADWICK PERISCOPE STUDIO

PERISCOPE STUDIO RonRandall.com

RonRandall.com THOMAS YEATES

THOMAS YEATES FAMILY MAN

FAMILY MAN MAD GENIUS COMICS

MAD GENIUS COMICS PERILS ON PLANET X

PERILS ON PLANET X QUANTUM VIBE

QUANTUM VIBE THE LAST DIPLOMAT

THE LAST DIPLOMAT THRILLBENT

THRILLBENT TRANSPOSE OPERATOR

TRANSPOSE OPERATOR

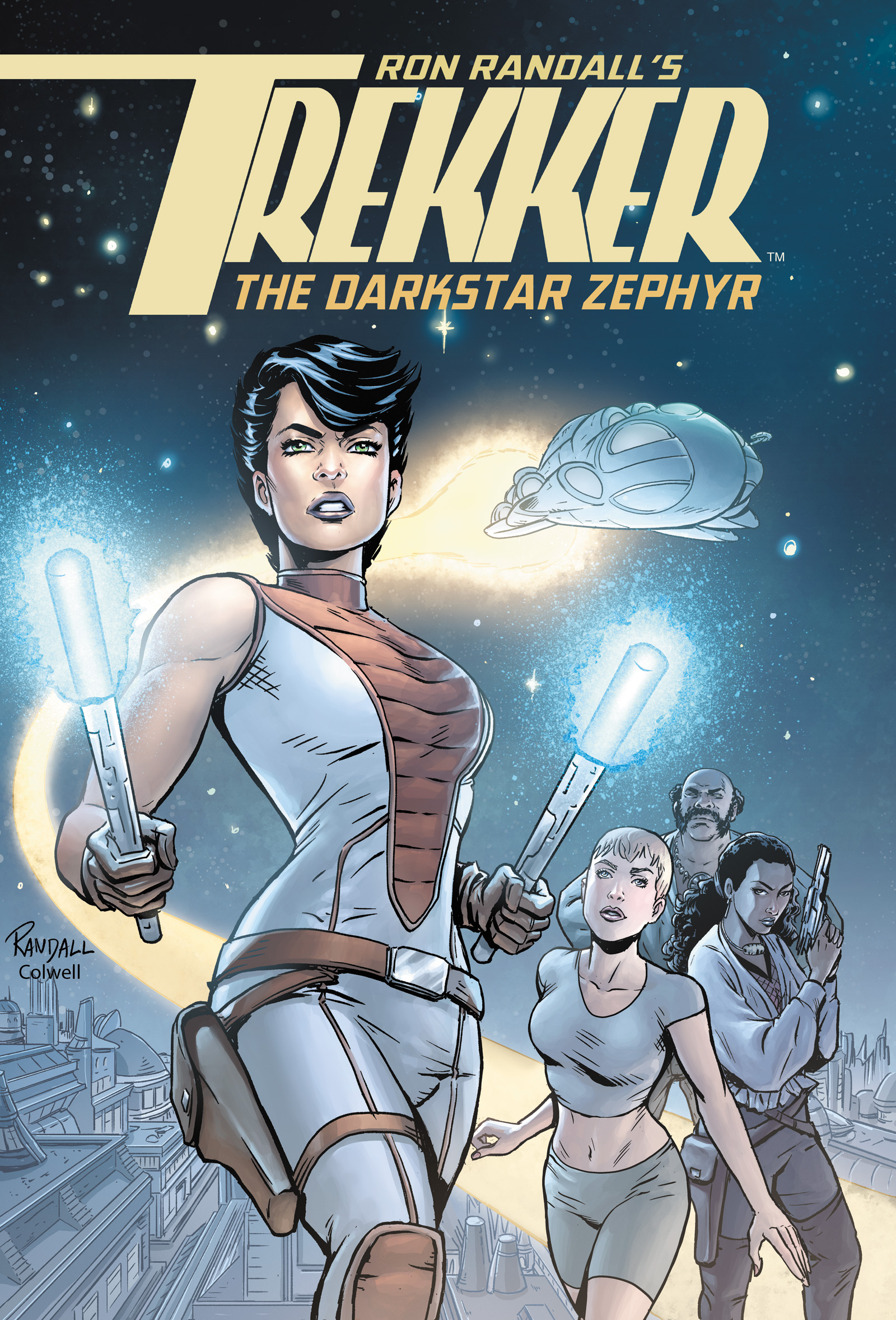

Happy to find your website/blog. I’ve been picking up the Warlord books recently, not for any fondness for the character, but because I truly enjoy your artwork and, most especially, your storytelling. Glad to see Trekker’s found a home online. Keep up the great work. I look forward to seeing more of it.

Regarding the seventies: I was immersed in the world of Charlton Comics mainly because of the quirky styles of artists like Tom Sutton, Sanho Kim, Pat Boyette, John Byrne and Joe Staton among others. I still love the work of those artists. But I did get up to speed on the rest of the comics world, discovering your work as well as Tim Truman’s, Walter Simonsson and Thomas Yeates. Great stuff, all of it. There are really so many artists out there to admire.

Thanks, Oscar! Glad you’ve found the site, and Trekker. As you poke around here you’ll probably see quickly that Trekker is my passion project. And fining any new reader is always a thrill. Hope you’ll continue to like what you read as Mercy’s stories continue.

I always liked Kaluta’s take on Madame Xanadu; his covers for Doorway into Nightmare were great.

A lot of people say the 70s were a “Dark Age” for comics, but there were tons of cool stories that came out back then. One of my favourites was Master of Kung Fu…great characters and not like anything else that was out at the time. Doug Moench’s writing was great and I loved Paul Gulacy’s art (and his successors, Mike Zeck and Gene Day were no slouches either!)

So right! Master of Kung Fu was indeed another great, unique title from that same era. I think it’s mistake to write off any time period with one broad stroke. There is always good work being done somewhere. Sometimes you just have to look a bit farther to find it.